Some of my early work explored epistocracy, the idea that those with greater competence should have more political power. I explored this idea from a philosophical perspective in Rethinking the Epistemic Case against Epistocracy. I looked at the argument that epistocracy will simply make decision-making worse; it would fail to include all relevant perspectives and therefore produce worse decisions. I argued that this argument is right but it needs a bit of tweaking; it needs to focus more closely on the epistemic costs of excluding already disadvantaged social groups (which is likely what epistocracy would do). In other work, I have explored epistocratic exclusion from a more historical perspective. In Precautions in a Democratic Experiment, I underscore different epistocratic mechanisms in the Indian constitution (and their links with British and Irish constitutional mechanisms).

I have also written several papers on political parties from a normative perspective. In Cracking the Whip, I started by outlining ways in which strict party discipline can harm legislative discussion. I argued that when party whips are too strict, this can reduce the epistemic capacities of the legislature, undermine the potential benefits of bicameralism (if there are any!), and reduce our capacity to engage in discussion across ideological lines. In What’s the Party Like?, I take up a related problem: if we assume that party discipline is constitutionally sanctioned (as is the case when a constitution forbids legislators from voting against the party whip), what does this mean for political parties? I argued that in such conditions, parties are best seen as quasi-legislative actors. And because they are quasi-legislative actors, they must work with some of the procedural norms that apply to legislators. Chief among these is that decisions must be made by many rather than the few. Consequently, parties in anti-defection jurisdictions must distribute decision-making power internally. And finally, in Intra-Party Democracy: A Functionalist Account, Samuel Bagg and I examine another feature which should affect how we think about intra-party organisation: a democratic system’s susceptibility to oligarchic capture.

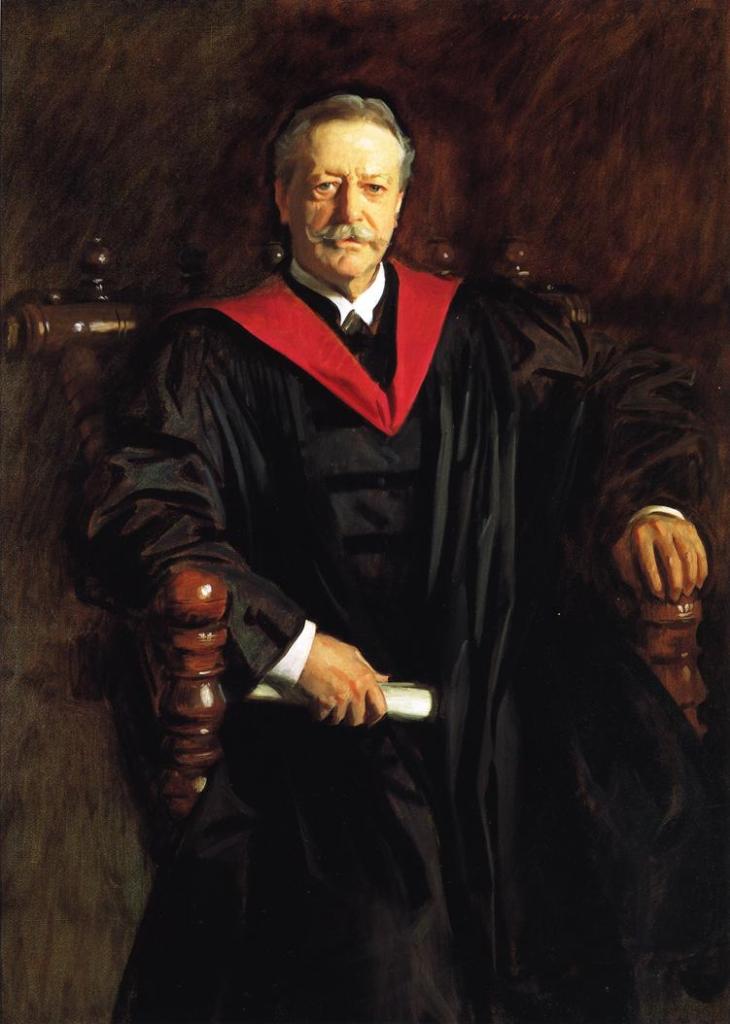

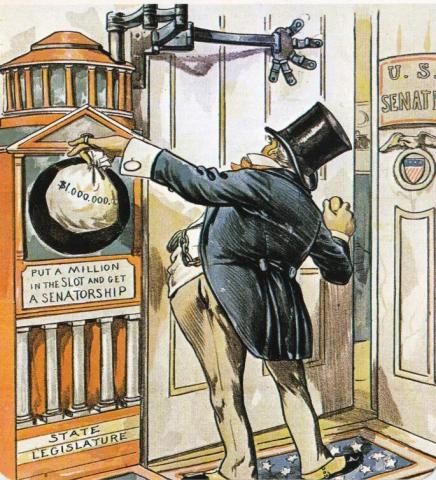

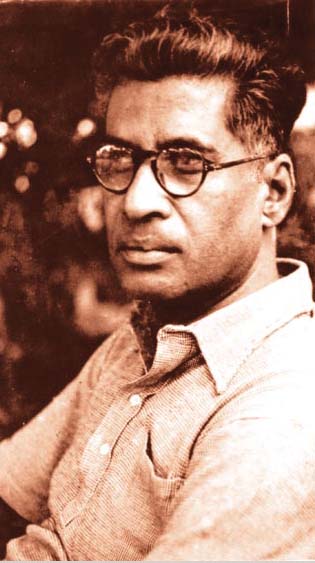

My most recent work brings together various threads of my work: party constitutionalism, epistocracy, and the history of democratic thought. In Indirect Elections as a Constitutional Device of Epistocracy, I explore the use of indirect elections in the US and India as ways of boosting the political power of those deemed wiser or competent. After exploring the thinking behind the epistocratic defence of indirect election, I discuss how this defence was affected by the rise of organised political parties. Here, I explore Progressive Era debates over indirect election and removal through the Seventeenth Amendment to the US Constitution. In The Pedagogical Account of Parliamentarism, I explore how parliament’s role was characterised by important figures at India’s founding. These figures, I argue, remained concerned about the unfitness of India’s electorate even as they were committed to universal adult suffrage. Their response was to view the legislator’s role in pedagogical terms, decanting their role in law-making. This conceptualisation, I argue, approximated mid-twentieth century British constitutional debates on party-parliament relations in some ways. Yet, it reveals an alternative strand of thought that marginalises parliament in favour of executive power.